America’s Finest: Clementine and the 1st Puss’n Boots Award

Dr. Paul Koudounaris is a historian, author, and photographer who has been regaling CatCon audiences with tales of cat hiss-tory for years. We’re pleased to present the first in a series of posts from Dr. Koudounaris about the storied Puss’n Boots Award, its recipients, and its impact on today’s cat culture.

In 1950 a cat arrived unexpectedly at the door of a Colorado home. This is of course nothing unusual in and of itself, as cats are well known for their unexpected arrivals into the lives of humans. But this was different. The arrival of this particular cat would forever change the history of the American feline, redefining the role they play in the lives of humans and ushering in the modern world of cat mania. This was a very special cat, you see, and while she may have been unexpected, she was not unknown… and she had come from very far away.

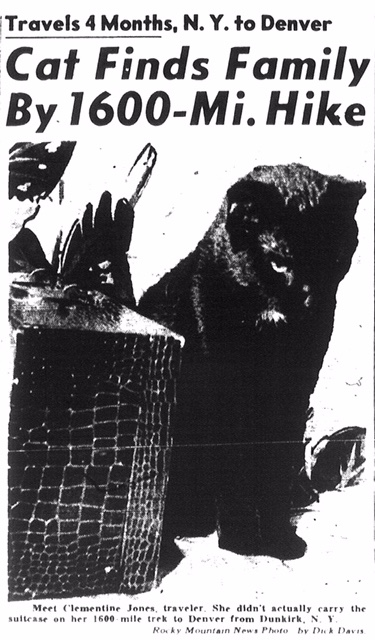

Clementine Jones in the Rocky Mountain News

Few remember her name nowadays, but in the magical fall of 1950 it was known throughout the country as a symbol of loyalty and devotion. Her human family, the Lundmarks, had been living in upstate New York but were uprooted in 1949 when Robert, the husband and provider, accepted a job at a department store in Denver. Moving across the country would be a big change, but the position he was offered was a good one, with a salary that would be enough to support a family.

But there was a problem. The Lundmarks owned a cat, named Clementine Jones after a once popular nightclub entertainer, and she was pregnant. Could a pregnant cat be moved so far without the trip being detrimental to the health of herself and the precious cargo she carried in her belly? Mr. and Mrs. Lundmark pondered their predicament and decided that while they did love their cat, it would be in her own best interests if . . . she were left behind.

Arrangements were made. Clementine was to take up residence with relatives near Buffalo in the town of Dunkirk. She could live happily there and raise her kittens. The goodbyes were sad, but it was the right decision as all agreed–all, that is, except for Clementine. She went along with the plan only so much as was necessary. Giving birth to her litter back in New York she cherished them as any momma cat would, but when they neared a year old and were well on their way to taking care of themselves Clementine hit the road. Stealing away like a thief in the night she snuck out of the house in Dunkirk. Somewhere out in this vast, wide land was her human family, and she had determined to find them.

There was scant evidence available to a cat regarding their location. Perhaps she had recalled seeing them leave and head to the west? In any event, that was the direction she herself headed. Back at the house in Dunkirk they of course had no knowledge of Clementine’s grand scheme, and when a cursory search of the neighborhood failed to turn up the missing cat they assumed the worst. And as days turned to weeks and weeks to months and there was still no sign of her, there was only one conclusion that could be drawn. A call was placed to the Lundmarks, who were now living in Aurora, 10 miles east of Denver, and the sad news was told: Clementine has been missing for several weeks and we’re afraid she must have been hit by a car or killed by a predator.

But the report of Clementine’s demise was premature, for in truth she was out there, somewhere, still headed west. Perhaps by that time in Illinois or Iowa, or maybe somewhere in Indiana? Wherever it was, suffice to say it was a long way from Dunkirk, New York. But to get all the way to Colorado? It would not only be a 1600 mile walk, it would involve some pretty savvy navigation. There were a couple minor impediments in her path–things like, oh, Lake Erie and Lake Michigan. She would need to know that to continue west she must first head south. And then there was the problem of the Mississippi River, which would have to be crossed.

There was no way a cat could make that trip. Or so conventional wisdom would claim. But cats pay little heed to conventional wisdom, and so it was that by early September Clementine stood at the base of the Rockies and began her ascent–upward, towards Aurora. And on the 18th of the month she walked along Navajo Street and stopped when the address read 1416, where the Lundmarks lived, in house she had never seen in a city and state she had never been. A cat had walked from New York to Colorado to find her family!

It was inconceivable–and so the critics claimed when the news first broke. Nice story, they said, in response to an article in the Rocky Mountain News trumpeting her valiant journey, but you clearly have the wrong cat there. She must simply be a stray who looks like Clementine. She was a black cat, after all, and black cats look more or less the same, folks. Ah she had a couple white spots as well? OK, but black cats with a few spots of white are not exactly rare either, they argued, accompanied by a certain condescension regarding the romantic naiveté of cat fanciers.

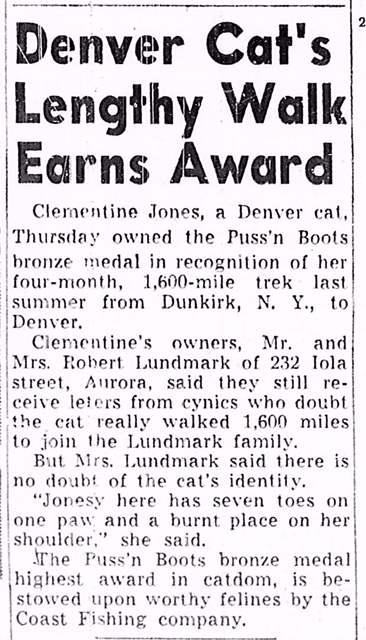

But the critics would soon be silenced by Clementine herself, because she carried with her proof as positive and any identification card. On one paw she notably had seven toes, and by the way, the pads on her paws were worn nearly to the bone from her 1600 mile trek. Proof was in the paws, and the cat who had shown up in Colorado could be none other than Clementine. Her doubters acquiesced and all acknowledged that a cat had completed an impossible journey to find her family. With the story confirmed the news wires told the whole country. It spread first through the Midwest and then to East and West Coasts, and in the fall of 1950 people all over America picked up their newspapers and read the tale of resiliently loyal cat.

A thousand miles away in the Port of Los Angeles the story was being read with more than casual interest in the offices of Coast Fishery. The company had found a use for the fish they hadn’t been able to sell to local stores–it could be ground up and canned as food for cats, distributed under the brand name Puss’n Boots. The feline market in those days was small compared to the canine, but sales of cat food had saved the company from bankruptcy. What a wonderful story Clementine was, the office staff thought. It shows what great animals cats really are. Someone should, to use the cliché, give that cat a medal.

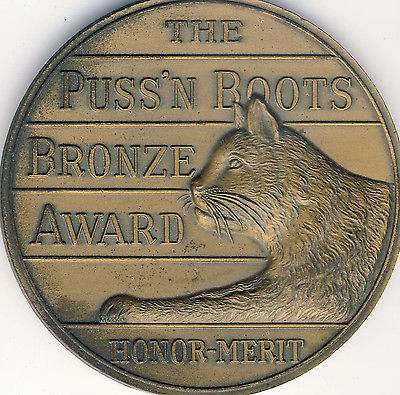

And they realized that wasn’t such a bad idea–hey, they could be the ones to give that cat a medal! A local sculptor was contacted: could he design a medal for cats? Nice looking, in thick bronze, about the size of a silver dollar coin? A proof was quickly struck, showing a recumbent cat with its paws outstretched, and bearing the inscription “The Puss’n Boots Award, Honor-Merit.” The medal was minted, and before you knew it was on the way to Aurora, along with a congratulatory note, arriving in early November.

Once again the newspapers carried the story, letting the nation know that Clementine Jones had received an award, but as far as Coast Fisheries was considered she was merely the first of what would be many. For they had minted not just one Puss’n Boots medal, but dozens, and decided that the award should stick around as a national medal of honor for felines. And not only that, from among the recipients one should be selected annually as America’s “Cat of the Year”–an added distinction to be sure, and one which brought with it a year’s supply of free Puss’n Boots cat food! Over the course of the next decade, as the accounts of the award winners hit the newspapers, they irrevocably changed the image of the American cat. Sometimes heroic, sometimes amusing, and always astounding, their real life stories touched an audience that had previously had been led to believe that only dogs could accomplish great things, and in the process they ushered in a golden age in American feline history.

Meet a hero sailor cat, a blind dog’s seeing-eye kitty companion, and other Puss’n Boots Award winners in part two of our series!

TICKETS ON SALE SOON