America’s Finest: The Legacy of the Puss’n Boots Medal

Dr. Paul Koudounaris is a historian, author, and photographer who has been regaling CatCon audiences with tales of cat hiss-tory for years. Last time he shared the story of Clementine, brave traveler (and cat) and the first recipient of the Puss’n Boots Medal. In this installment, meet a hero sailor cat, a blind dog’s seeing-eye kitty companion, Bebe, feline head of her local election board, and learn how they all paved the way for our modern Cat Age.

It would of course be ingenuous to not see in the introduction of the Puss’n Boots medal an obvious marketing ploy. After all, it bore the name of a cat food company, so the newspaper articles noting the award bestowed upon Clementine and all those who came after served as a form of free advertising. In addition, by raising the prestige of felines among the American public, Coast Fishery had every reason to expect more people would take cats as companions. And more cats in more homes meant, well, more potential customers for their product.

But even with such suspicions confirmed, there was more to the introduction of the medal than crass marketing. That Coast Fisheries had decided to do so in 1950 was meaningful, because it was a time that was ripe for the ascension of the cat. Only a year prior a cat named Simon, adopted off a Hong Kong dock by the crew of the Royal Navy gunboat Amethyst, had been credited with saving the lives of his crewmates. Sent up the Yangtze River to evacuate the staff of the British Embassy in Nanking during the Communist takeover of China, the ship was ambushed and disabled by enemy artillery and stranded in enemy territory.

There was no hope of relief without the possibility of a full scale war, and when rats started invading the hull and preying on the minimal provisions in the hold, the crew would have been done for–save for Simon. The little black and white cat understood the precarious position his friends were in and positioned himself an impassable barrier. He dispatched every rat with the temerity to encroach upon the Amethyst, and even as the months wore on to three in total vigilant Simon maintained his post to ensure the ship’s limited rations were stretched as long as possible.

Meanwhile, his human crewmates were patching their vessel and refitting the engines, and under the cover of the night the long dead engines came to life, and the Amethyst made a daring run to freedom. From the high seas word spread of the role of the ship’s cat in the crew’s survival and at every port of call en route to England bags full of mail sent from around the world were presented to Simon–letters of thanks, cards congratulating him for his heroism, gifts and treats from admirers. He soon found himself the recipient of the Dickin Medal, the animal equivalent of the Victoria’s Cross, the only cat ever so honored, and the Royal Navy even bestowed upon him an official rank: “Able Sea Cat.”

With such hoopla Simon had positioned himself as the first international feline celebrity. And he had done so by proving that cats were capable of the same heroic, loyal, resilient things that were thought to be province only of dogs as man’s best friend. For cat lovers around the world, Simon was celebrated as an icon to which they could point and say, “see, I told you how great cats are”–and for cat haters, he was a perplexing conundrum that forced them to acknowledge, “well, OK, I guess sometimes they’re not that bad.” The first half of the twentieth century had been the golden age of the dog and cats walked far in their shadow, but Simon’s story shook that foundation.

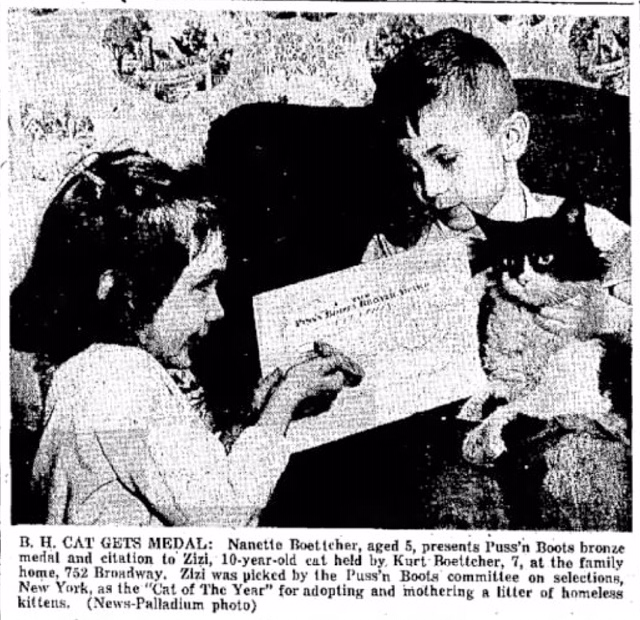

And when Clementine Jones found her family she didn’t just walk to Colorado. She had in addition walked on behalf of a nation’s cats of the shadow of the dog. Here was our own down home feline who was as dauntless as Simon, one who could fill the role of hero for American cats, and Coast Fishery knew that the with a little push felines might just steal center stage from canines as the nation’s favorite. It was, in effect, the dawn of the age of the cat, and as if on cue America’s felines responded. Stories were suddenly coming in from nearly every state about their achievements, each one seemingly more amazing than the next. It’s hardly an exaggeration: so many medals were being awarded that Coast Fishery had to appoint a special panel in New York to oversee the promotion, as they simply couldn’t handle it from their little office in the port.

Some of the stories could warm even the coldest heart. When an elderly plantation dog went blind in Louisiana, there suddenly appeared on the property an angel of mercy in the guise of cat who came to be known as Kitty Billy. He was a stray, but somehow sensing the dog’s plight he ceased his own meanderings and began waiting outside the house. When the blind dog would emerge, Billy would walk with it and act as its eyes, helping it along safely, crossing streets, and making sure it eventually found its way home.

The newspapers loved it. A seeing eye cat! Billy’s medal was well deserved, but just as remarkable was what he did after: when the old dog passed away, Billy left the property and never returned. He had halted his own wanderings in order to care for an ailing creature, and while the plantation was more than willing to take him in, he wished no home from man as thanks. His mission now completed, he left his medal behind to continue with his own life’s journey. A selfless hero if ever there was one!

From Joplin, Missouri, came the story of a cat who adopted a litter of baby opossums. They were only a few days old when they were discovered by a Humane Society worker in the pouch of their mother, who had been hit by a car. Five baby opossums in dire straits . . . they were taken to the local animal shelter where they just so happened to be a cat that had recently nursed her own litter of kittens. And Mother Sue, as she would come to be called, stepped in to save them, keeping them warm, suckling them, raising and protecting them as her own. Her medal arrived during Be Kind to Animals Week, since she was judged a symbol of the harmony that can exist within the natural world.

Another heroic momma cat was found in Reseda, California. A local stray nursing some newborns had her littler stolen by a gang of boys–tragic enough, but even more so because she was discovered by the Dubers family with a swollen belly and in extreme pain. She had been generating milk, but without her newborns to suckle she was unable to discharge it. They took her home and called a local vet. It was possible to perform an emergency operation and release the fluid they were told, but it turned out to be unnecessary. Their own family cat, Susie, had a litter of four, and picked up two by the scruff of the neck and carried them over to her ailing counterpart and coaxed them to nurse. Susie had not only correctly surmised the situation, she had offered her own kittens to aid a cat in need. And in fact, made a permanent gift of them: the mother cat that had been deprived of her own kittens was allowed to stay in the home and keep the pair as hers.

Other cats received medals for their direct service to humankind. A Hagerstown, Maryland cat named Sandy became a hero after waking her family and saving them from a house fire. Bebe of Torrance, California, meanwhile, received a Puss’n Boots Award when it was discovered that she had been serving for several years as the head of the local election board, having been appointed in the 1940s. Every vote counts, after all, and Bebe was on duty to make sure the counting was fair. And up at San Quentin penitentiary lived a kitten named Chickie, the darling of the inmates, who had constructed for her a toy piano, a mini bed and dinner table, and a toy hot rod which she road around the prison yard. A letter of congratulation was sent by Coast Fishery care of the prison warden, thanking Chickie for brightening the lives of 2000 men, and the presentation of her medal was a cause for celebration shared equally among the prisoners and staff.

There were also cats whose victories were a little harder to figure–although perhaps from a feline perspective their accomplishments were equally noteworthy. Felix, a tiger tabby in North Adams, Massachusetts, received a medal after he barged into a courtroom in the midst of a trial, and rather than recuse himself instead chose to jump onto the tables of both the prosecution and defense attorneys and scatter their papers into a large pile on the floor. Another was awarded to a Siamese named Ming who snuck into a Southport, Connecticut, church on a Sunday morning. When the choir began to sing, he joined in, howling in such a loud and alarming voice that the congregation feared the Devil was in their midst. And a cat named Squeaky in Laurel Run, Pennsylvania demonstrated a novel new treatment for the control of fleas: he liked to be vacuumed, and would allow his human family to suck the fleas right off him with their high powered Hoover. What an idea! Might other cats go for it too?–no, but Squeaky received a Puss’n Boots medal anyway.

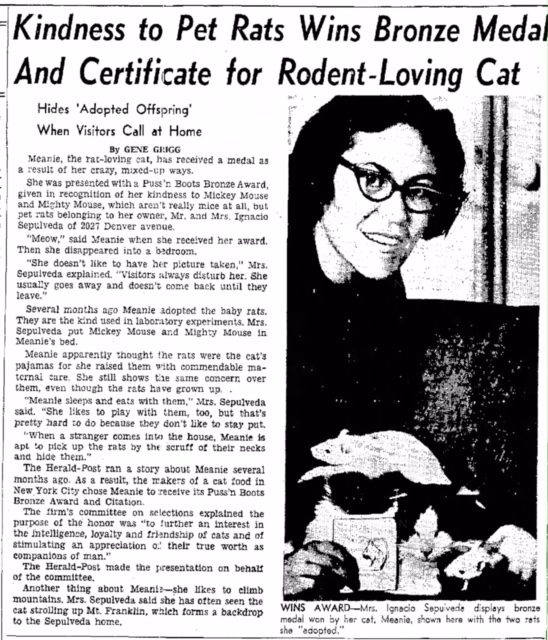

The publicity surrounding the Puss’n Boots medal winners bolstered the status of the American feline, and it also crossed borders, not only between states buts within society. In an era where traditional hierarchies of class and race still held firm, the winners were coming from families of almost every conceivable place, race, and class–proving clearly that the love of cats knew no bounds. In the process, humble neighborhood cats were being elevated to celebrity status, the beginning of pop culture’s obsession with feline idols.

Of course, it was not the kind of celebrity than we’re familiar with now. There was no internet to spread their fame, no YouTube to entertain millions with their antics at a click, and no Instagram to provide the dopamine high of Likes. Compared to modern celebrity cats the fame of the Puss’n Boots winners might therefore seem paltry. But it was a different era–every city had its own newspaper, even small towns did, religiously read by residents, and it was there that these cats were heralded. A Puss’n Boots winner was a big deal! It was news to be known, a source of pride for the entire locale. It was a kind of celebrity that functioned on a microscopic level, and while people even a few counties away may not have heard a word about it, you can bet your bottom dollar that for, say, the people in Hagerstrom, Sandy who saved her family from that fire was a bigger star than any Instagram cat could ever be.

There was another important difference between the feline celebrities of those days versus the modern variant. Nowadays cats are deified largely based on looks–a feline with a particularly fetching or unusual appearance can, with the right photos and the right breaks, ascend to that upper echelon of feline celebrity. But there was an ethic to those Puss’n Boots winners, and there was nothing superficial about it: no cat ever won the award for the way it looked. In fact, in most cases the panel awarding the medals would have no way of knowing if they were selecting the most attractive cat who ever lived or a mangy, cross-eyed troll. And they didn’t care, because a Puss’n Boots medal had to be earned, and the only way to do that was through actions that demonstrated a cat as being of exceptional merit. Hence the inscription on the verso of the medal, a caption explaining that for “contributing to human happiness and exhibiting other admirable traits,” the award winner has “further elevated the cat as man’s friend (and) loyal companion.”

Sadly for America’s cats, the Puss’n Boots medal had a short lifespan. This was an era that saw the growth of mega-corporations, as conglomerates fought to achieve monopolies by buying out smaller companies and assimilating their brands. Little Coast Fishery fell prey to bigger fish, to be bought and bought again. Puss’n Boots cat food continued to be sold through the 1950s, and since for the better part of the decade was still being manufactured by what was left of the original company the medals likewise continued to be awarded. They were presented with less frequency as the decade passed, however, since the larger companies that took over the brand might be fully in favor of selling cat food, but were skeptical of spending the time, money, and effort to award America’s finest felines with bronze medals. The latest record I can confirm of a medal being awarded was to a cat in Anniston, Texas, in January of 1960, and the coup de grace came soon after. Quaker Oats had taken over the brand by that time, and there would be no more medals. In fact, there would be no more Puss’n Boots cat food, as the brand itself was terminated–although the name was available for licensing, and would periodically pop up again even into the 1970s, although the product would have been coming from random meat packing plants that had paid a usage fee.

Exactly how many medals were given out during the decade after Clementine Jones made her triumphant appearance in Aurora is a vexing question. The number of cats to be acknowledged is no doubt in the hundreds, with the most complete extant records dating from 1950 to 1952, before Coast Fishery was first sold. Proud of its promotion, the company had during at that time created certain materials including a bound pamphlet detailing various of the Puss’n Boots winners, but a complete roster from even those early years does not exist. And thereafter the fishery’s own internal records were apparently transferred with each successive sale. Most likely the company records related to the medals were disposed of, and even if they weren’t they are for all intents and purposes lost (for kicks try calling Quaker Oats sometime and tell them you are doing archival research on cat medals from the 1950s and see how far you get–OK, I’ve done exactly that so I’ll save you the effort: you won’t get very far).

The small town newspapers that heralded the fame of these cats likewise fell prey to bigger enterprises. By the 1960s they were being bought out and assimilated by larger newspapers, and these in turn were purchased by news conglomerates that owned scores of big cities papers. For news corporations there was little interest in local editions with low circulation numbers so the small town papers were discontinued entirely. This happened before the digital age, so only a fraction of them were ever scanned and uploaded to the internet–sorry folks, but if you’re looking for Puss’n Boots winners Google can’t help you much.

Take the case of Bebe, the Torrance election cat. Her story was originally carried by a city newspaper, which then was then taken over by the regional newspaper Daily Breeze, which was in turn purchased by the Gannett news group, and then traded in a swap of assets to Digital First Media, which is owned by a New York hedge fund. In the process the original daily containing Bebe’s story, like those of many of these cats, was left far behind, packed among boxes of tattered old newspapers moved to a library storage rooms due to lack of circulation. Some of the stories may have by now been lost entirely and others survive only in scant few copies–I suspect that the San Quentin newsletter in which I found with the original photos of Chickie is the only one left in the world, considering that the prison itself does not have a copy and neither does the California State Library.

In the end, the Puss’n Boots winners ran off and hid from us–although I suppose it’s the feline way, since cats are very good at hiding after all. But while the original cats may have retreated back into the shadows of history, the sun shines brightly upon their progeny. American cats are more popular, more beloved, and more esteemed than they have ever been. Who would have guessed when a dauntless cat showed up on a doorstep in Colorado nearly 70 years ago wanting only to find her family, and a little fishery in Los Angeles in turn decided to give her a medal, that a new age had dawned? But together they had added their own little pieces to history, and when the cats who followed soon after Clementine Jones added their little pieces in addition, it added up in the end to a very a big piece: they had given America the Age of the Cat.

TICKETS ON SALE SOON